Fascinating and Interesting Alpaca Facts You Should Know

Discover interesting alpaca facts about their history and significance as livestock in modern societies.

Although alpacas and llamas are ancient livestock in South America, the’re also the newest form of livestock introduced in industrialised countries. They can justly be called the livestock of the 21st century. In the 19th Century alpacas were rediscovered by Europeans and played an important role during the Industrial Revolution. Sir Titus Salt discovered the unique aspects of alpaca fibre and went on to earn a fortune and establish a town dedicated to its processing (Saltaire, in Bradfordshire, England). Sadly, he can also be blamed for the near-destruction of coloured genetics among alpacas world-wide, because that’s where that ridiculous notion emerged that white fibre of any kind is preferable, as it can be dyed into any colour, and farmers were happy to oblige in the hope of getting a better price for their fibre.

In 1853 there was an unsuccessful attempt to export alpacas to Australia. Thomas Holt, who decided to import alpacas, llamas and vicunas, commissioned Charles Ledger, a Peruvian merchant to look for suitable animals.

Known simply as Alpaca, many references can be found in popular literature of the 19th and early 20th Century. While few may have been aware of the animals, fabric and finished goods were well known and viewed as a luxurious and valuable commodity. Alpaca remained in demand until the development of synthetic fibres in the mid-20th Century began to supplant natural fibres, at which point both alpacas and their fibre once again largely faded from the public’s awareness.

After the Spanish conquest, alpacas were nearly wiped out. By some accounts, 90% of the alpaca herds were destroyed in an effort to subjugate the native peoples, and as part of the drive to squash all memory of the Annunaki overlords, biblically referred to as the ‘gods’.

ORIGINS – South American Camelids (SACs)

Alpacas are part of the camelid family, in the suborder Tylopoda. This suborder is divided into two groups – Old World Camelids and New World Camelids. Old World Camelids include the bactrian and dromedary camels, while the New World Camelids include the alpaca, guanaco, llama and vicuna. The domestication of alpaca and llama is believed to have occurred approximately 6000 years ago, when they were considered the Anunaki ‘gods’ preferred fiber. Vicunas and guanacos were never domesticated animals, and still roam wild in South America.

The New World Camelids are referred to as South American Camelids (SACs) and are collectively referred to as lamoids. Much controversy existed over the years as to how these SACs should be classified.

It is widely accepted today that alpacas, llamas and guanacos are species within the genus Lama, while the vicuna is classified as a species within the genus Vicugna. All members of the camelid family (including camels) have the same number of chromosomes (2n=74) and produce fertile hybrids (crosses).

Alpacas

Alpacas (paqocha in the Quechua language) has a smaller and more curved silhouette than llamas, and has a classic fibre apron on their chest. Alpacas come in at least 16 recognized colours, with endless shades and colour patterns in-between. Alpacas reach a height of 150 cm and weigh about 68 kg. A new-born alpaca, known as a cria, weighs about 6.5 – 9kg.

Alpacas generally carry more fibre than llamas, producing anywhere from 1.7 – 5 kg per year. Alpaca fibre averages 25 microns in diameter, but the fineness of its fleece is directly related to the age of the alpaca. The finest alpaca fibre comes from the first shearing and is known as “baby alpaca”. Older alpacas may also have such fine fleece, and it will still be classified as baby alpaca.

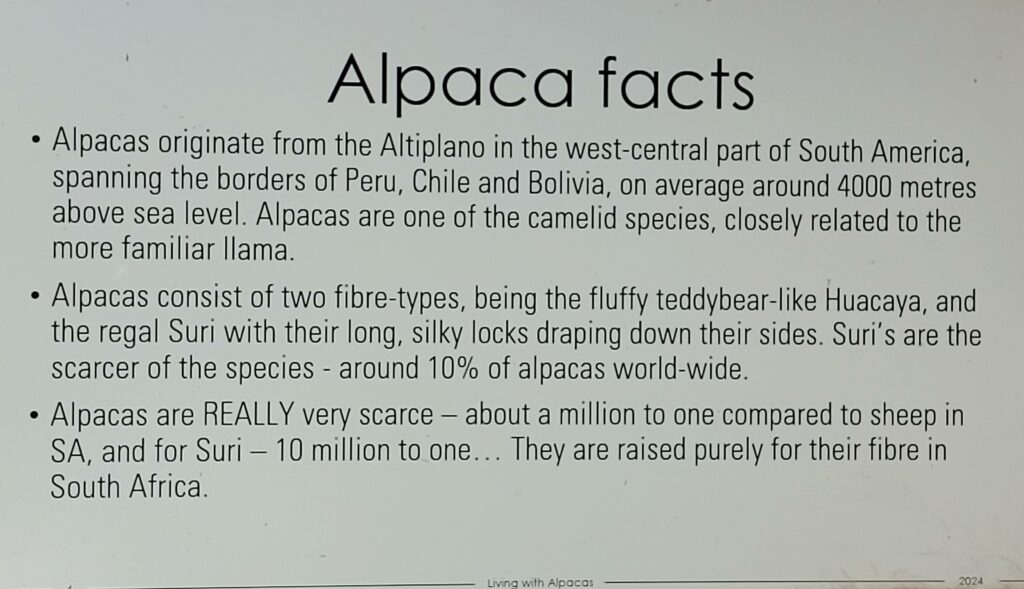

Alpacas consist of two recognized breeds, Huacaya and Suri.

Huacayas have a dense, springy fleece covering almost their entire body, in the typical teddy-bear or sheep-like appearance. Suris have sleek, silky and long fibre, draping from its sides in curly locks, which may reach a length of 16cm. Alpacas are traditionally shorn every year.

Alpacas are relatively new in South Africa.

There are roughly around 3000 alpacas in South Africa, of which around 200 are Suri alpacas. In comparison, there are 21.43 million sheep in South Africa.

When compared to Australia, who imported their first alpacas about 10 years before South Africa, there are around 350,000 alpacas in Australia, quite a lot down from the 800,000 when they officially decided to start slaughtering/’harvesting’ them for their meat around 2012. Yes that certainly sets the Alpacalyps in a new light… Australia also has around 76.5 million heads of sheep in comparison.

New Zealand have around 25.13 million sheep, and around 20,000 registered alpacas, 10% of which are Suri. Peru, their country of origin, has around 3 million alpacas, approximately 90% of the world’s alpaca population.

Suri

Suri Alpacas are distinguished by their beautiful distinctive heavy, shiny, long and lustrous flowing locks of fleece, similar to the fleece of an Angora goat. Suri alpacas have unique fibre characteristics that distinguish them from Huacayas, and are known for the lustre and drape, most often seen in woven fabrics. Unlike the soft fuzzy ‘teddy-bear’ look of the Huacaya, Suri locks are comprised of twisted or flat fibres that are draped down parallel to the sides of the Suri’s body, leaving its back line bare. The lustre in Suri fleece is the primary indication of its quality. In addition, the fibre should be fine, have a good handle and a pronounced silky feel to it.

Suris make up less than 8% of the global alpaca population (some say it may even be as low as 2%). If it weren’t for the many farms around the world breeding them, they may be considered an endangered species. They are so rare, there may be fewer of them than the vicuna, the wild ancestor of the alpaca.

The ideal Suri fibre is composed of well-defined and tight locks. These characteristics are important to preserve the phenotype, as well as to facilitate in fibre processing. The Suri’s fibre has a cool, slick feel, soft as cashmere, warmer than wool, with the inherent lustre of silk.

The spirals or pencils could be twisted to the left or to the right. These spirals or locks can consist of waves or curls of great size and length. In South America, and the world-wide alpaca show circuit, Suris are often left unshorn till the end of their second year, to be able to fully appreciate their full fibre splendour, with locks sometimes even touching the ground. These extra-long locks are in great demand in ‘reborn’ doll-making, where the locks are used as hair for those incredibly life-like baby dolls. Tuis (2-year old) Suris with full-length flowing locks are a sight to behold when you see them running accross the fields. Truly breathtaking, but in South Africa this will not be easily achieved, we have way too hot a climate, and it will be a terrible punishment for the animals.

The ideal Suri alpaca has a squared off elegant appearance with four strong legs. It is a graceful, well-proportioned animal with its head and neck representing one-third of the body size. The Suri’s head is slightly narrower than the Huacaya’s, rather horse-like, and their ears are one to two centimetres longer. It is well covered with fibre from the top of the head to the toes.

The Suri breed is said to be more resistant to nutritional changes than the Huacaya, but more susceptible to changes in the environment. They are less capable of coping with very cold and wet weather, as their open back line allows for greater heat loss and water seepage. That may also be why they seem to cope better than the Huacaya in our hot bushveld climate.

Because of its rarity, fine Suri fleeces are currently the highest paying alpaca fibre on the international market.

Huacaya

Huacaya (pronounced “wuha-kaya”) alpacas are the more common of the two fleece types. They have fluffy, crimpy fleece that gives the animals their much loved teddy bear-like appearance. They are famous for the abundant growth of crimpy fibre on their legs, neck, forehead, and cheeks. Their fibre is dense and stands perpendicular to their body, much like that of sheep. They are by far the most common type, constituting more than 90% of the world’s population.

The Huacaya’s dense, fluffy fleece makes it perfectly adapted to the harsh climate of the Andean highlands, where temperature swings can be extreme. Some theorize that the prevalence of the Huacaya type is at least in part the result of their native climate, suggesting the Suri type may have been more common prior to the Spanish conquest, when they were tended at much lower elevations than where most alpacas are found today.

The most sought after traits in the Huacaya are density and fineness of fleece. These traits can be extremely difficult to attain simultaneously, as it seems fineness and density are somewhat antagonistic. Still, significant progress has been made in breeding Huacayas with high yields of sub-20 micron fleece in recent years.

The ideal Huacaya alpaca has a squared-off appearance with four strong, well-proportioned legs. They are graceful animals with the neck and the head representing one third of the body size. They are well covered with fibre from head to toes. Their huge soulful eyes are black, their ears are spear shaped, not the typical familiar banana shaped ears of llamas, and their appearance is proud and straight.

The sheep-like fleece of the Huacaya is characteristic, giving them a more robust, chubby appearance when compared to the Suris, which are more reminiscent of a horse than a sheep.

Huacaya are believed to be more resistant to diseases and severe climate changes than the Suri. They certainly are able to withstand much colder weather than the Suris, as they have the very best in fur coats, including super thermal insulation!

Huacaya alpacas should be well covered with a soft, uniform fleece, except on the ears and the bridge of the nose of mature animals. It should have well-defined crimp from head to tail. The perfect Huacaya will have fine, dense, uniform fleece growing perpendicular to the skin, as soft as cashmere, with superb crimp and sheen.

The life span of an alpaca ranges from 20 to 25 years. Suris tend to mature slower than Huacaya. Males usually begin breeding when they are about two years old (Suri’s around 3), at which time they are called “machos”. Females can be bred when they weigh around 43 kilograms. This generally occurs around the age of 14 to 18 months of age, at which time they are called “hembras”. Females are induced ovulators, so they can be bred year around. Following an 11 ½ month gestation (335 – 342 days), they give birth to a single cria that weighs between 7 and 10 kilograms.

Llama

llamas are the most common and also the strongest of the Andean camelids. They have a slender shape, and may be found in as many as 50 different colours. Llamas have elongated legs, neck and face, and may reach as high as 188 cm from the ground to its head. Its long ears are erect and curve inward in the classic banana shape. As a pack animal, the llama can carry a weight of about 40 kg for long journeys, and up to 60 kg on short trips. The average weight of an adult llama ranges from 115 – 180 kg.

Llamas are “beasts of burden”. They are used for carrying loads on their backs in special packs, like the Dromedary and Bactrian camel. Although not considered a fibre producer, llama fibre is used a lot in South America. They have a very soft secondary undercoat, with stronger primary fibre on the outside. Some llama are very coarse, others can be silky and lustrous.

Vicuna

The vicuna, the wild ancestor of the alpaca, is the smallest of the Andean camelids, reaching a height of 130 cm. They are very agile, and have a thin and slender body. With a light brown back, the vicuna’s inner legs, belly and chest are whitish in colour.

Alpacas’ ancestors are the wild vicuna. Vicunas represent the spirit and life blood of the camelid families living in the high Andes. Sadly, their extremely valuable fleece ensured vicunas were nearly hunted to extinction by the late 1970s. Conservation efforts in Peru, Chile and Argentina have led to a phenomenal resurgence in vicuna populations. Once again, due to careful management, vicunas can be found in healthy numbers in the Andes.

Vicunas (Vicugna vicugna) are members of the Camelidae family, of which there are three other living members in South America: the wild guanaco (Lama guanacoe), the domestic llama (Lama glama), and the alpaca (Lama pacos).

The smallest of all camels, the vicuna stands just under 90 cm at the shoulder. Like all South American camel species, the vicuna has a long, supple neck; slender legs; padded, cloven feet; large round eyes; and a dense and fine tawny coat.

The vicuna is a hardy survivor adapted to high altitudes, where drought and freezing nights are the rule. It is a natural pacer and well designed to travel fast over great distances. Keen eyesight allows early detection for flights to safety.

The vicuna is the probable wild progenitor of the domestic alpaca, which was created by selective breeding about 6000 years ago. Entirely wild, vicunas live in small family groups led by a single territorial male that vigilantly wards off rival males and small predators threatening the young. After 11 months of gestation, vicuna mothers give birth to one baby, known as a cria.

Vicuna weigh about 5kg when born, and about 40kg as adults. Vicuna fibre is the finest among all the animal fibres with an average diameter of 12.5 micron, but it is short, hardly reaching 3cm. Its annual fleece can reach a maximum weight of 300g.

The vicuna, producing such a fine fibre, was coveted and hunted to near extinction. Today the Peruvian government officially protects this species in special National Parks. In reality, damage to this species continues as poachers slowly decimate the remaining wild herds. The world-wide population of vicuna is less than 170,000, of which some 100,000 are found in Peru in regions that are over 3800 meters altitude.

Vicunas (alpacas too) are highly communicative, signalling one another with body postures, ear and tail placement, and numerous other subtle movements. Their vocalizations include an alarm call — a high pitched whinny — that alerts the herd to danger. They also emit a soft humming sound to signal bonding or greeting and a range of guttural sounds that communicate anger and fear. “Orgling” is probably their most unique noise. This male-only, melodic mating sound attracts unbred females.

Guanaco

The guanaco, the wild ancestor to the llama, has a similar silhouette to that of its modern counterpart, with a light brown-reddish dense and short fur, and with blackish tones on the head and whitish zones around the lips, the ears’ edges and inside the legs. They are not considered to be of economic value, and live in an entirely wild state.

ALPACA FACTS

Life Span: 15 – 25 years

Height: 80–100cm at the shoulder

Weight: 55–90kg

Gestation: approximately 340 days

Alpaca are believed to have evolved from the wild vicuna and are generally smaller than the llama, standing at just under a metre at the shoulder. They produce a magnificent, heavy fleece of fine strong fibre that comes in 22 ‘official’ basic colours including whites, fawns, browns, blacks and greys, and many other shades in-between. A fully fleeced alpaca with good coverage around the face and legs is truly a sight to behold, and definitely one of the reasons why so many farmers have decided to enter the industry, and many other people have changed their lifestyles to accommodate these beautiful creatures in their daily lives. One look into their huge dark soulful eyes can melt even the hardest heart.

They are relatively small (55–90kg and 80–100cm tall at the shoulder), long lived (±25 years), and easy to handle, and make delightful companions. They are intelligent and quick to halter train and lead. They are unique in appearance, yet share several traits with their camelid cousins, llamas and camels. Camelids are a modified ruminant, not only eating less grass than most other animals but converting it to energy very efficiently. Unlike true ruminant, they have three compartments to their stomach, not four. Camelids are therefore able to survive in areas that would otherwise be unsuitable for other domesticated animals. They are disease resistant and generally do well on good quality grass hay where sufficient pasture is unavailable. They are gentle on the land and stocking rates are up to 10/ha of pasture and more if their feed is provided through other means. People with no previous experience with livestock are successfully raising alpacas all over the world.

Alpacas are gentle and intelligent animals, and can certainly not be compared to sheep. They are social animals and are happiest when kept with other alpacas (while they have been successfully run with sheep or goats, a lone alpaca will show signs of stress, and generally won’t thrive). Alpacas can produce one offspring per year and can have up to 20 during their lifespan.

Birth: A single baby, called a “cria” is normally delivered without assistance during the morning hours up to around mid-afternoon. Later births usually indicate something’s amiss, and assistance may be required. Luckily, this isn’t often the case. Twins are rare, occurring once in about every 2,000 births.

Crias weigh 6.5 to 9kg at birth and can usually stand to nurse within the hour. They are weaned at 5 – 6 months after which they are called “tuis” until they reach breeding age.

Fibre: Alpaca fibre is softer than merino and has a higher tensile strength than sheep’s wool, creating a far more durable garment. There is a lucrative niche market for this luxurious, resilient fibre internationally, and with the current developing fibre market in South Africa, we hope to see the demand and use of alpaca fibre increase in the next few decades.

The main trait required by breeders in the alpaca breeding industry, and specifically in huacayas, is crimp. Internationally, judges look for fineness, and in Suri, locks and lustre lead the way; we however believe a superior fleece to be a perfect blend of all the different traits mentioned above.

Alpaca fibre is considered one of the finest fibres in the world. It also boasts some exceptional natural attributes that explain alpaca’s high demand in the international markets. These attributes include great fineness, 3.7 times superior to lamb’s wool, handle, thermic, hypoallergenic, and fire retardant and with over 22 natural colours to choose from.

Most important to hand-spinners though, is the fact that it lacks lanolin. So processing compared to sheep’s wool is a breeze! Lanolin also seems to be the biggest culprit in skin allergies, so this may be one of the reasons alpaca fibre scores so high as being an almost allergy-free fibre.

Alpaca fibre may measure between 15 and 40 microns and is partly hollow which accounts for its lightness. Human hair often exceeds 100 microns.

In South Africa alpacas are usually shorn from late September/November, before the onset of our scorching summer weather.

Fibre yields in South Africa vary from animal to animal but is often between one and a half kilograms to three or four kilograms annually. In colder climes a higher yield would be achieved.

Colour: Alpacas come in 22 “recognized” natural colours, but countless variations exist. These colours range from pure white, to various shades of fawn and brown, through rose and silver greys, to black. In addition to the 22 natural colours, the lighter fleeces also have the advantage of being readily dyed.

Health: Because alpacas and their ancestors are especially suited to the harsh environment of their Andean homeland, alpacas are generally healthy, easy to care for and remarkably disease free.

Hygiene: They are picky in their habits and will tend to form communal dung piles, which assists in maintaining a clean living environment and controlling the spread of parasites. Generally, males have much tidier, and fewer dung piles than females who tend to stand in a line and all go at once. One female approaches the dung pile and the rest of the herd often follows. Because of their preference for using a dung pile, some alpacas have been successfully house-trained.

Socialising: Alpacas are social herd animals that live in family groups, with everyone looking out for each other. Alpacas warn the herd about intruders by making sharp, high pitched shrieking sounds.

The herd may attack smaller predators with their front feet, and can spit and kick. We have picked up trampled dead snakes in the paddocks. Some alpacas have the capability of spitting, and some actually seems to have turned that into an art form. I have been on the receiving end of many an unpleasant glob planted right in my face, or spread over my body, depending on the angle of the ‘attack’. And believe me, shearing time for some of them is a dreaded time for the people trying to collect the fleece. You need a facial screen… The Suris seem to have turned this into a fine art form. The “SPIT” is brought up from the acidic stomach and is generally a green grassy mix with a little bit of saliva, and it smells every bit as gross as it sound!

Alpacas mainly spit if they feel threatened, and they mainly spit at each other, but they will spit at humans if they fell threatened by them. After an alpaca has spat they have what is called a “Frozen Lip” – the bottom lip hangs. This happens because of the unpleasant taste and the high amount of acid that has passed through their mouth.

Sounds: Alpacas make a variety of sounds. When they are in danger, they make a high-pitched, shrieking whine. Some breeds are known to make a “wark” noise when excited. Strange dogs—and even cats—can trigger this reaction.

To signal friendly or submissive behaviour, alpacas “cluck,” or “click” a sound possibly generated by suction on the soft palate, or possibly in the nasal cavity.

Individuals vary, but most alpacas generally make a humming sound. Hums are often comfort noises, letting the other alpacas know they are present and content. The humming can take on many different meanings.

When males fight they scream a warbling bird-like cry, this is intended to terrify the opponent. I believe the raptor sounds used in the dinosaur movies may have been copied from alpaca screeches

ALPACA BEHAVIOUR

Alpacas demonstrate a “striding” gait unique to camelids. Rather than walking with alternating front and back legs, they will lift both legs on the same side when walking forward. (Camels also walk this way, creating a swaying motion that has led to them being called, “The ships of the desert.”)

Alpacas are herd animals and will generally stay in close proximity to each other. In fact, an early sign of illness in an alpaca will often be that they have separated themselves from the rest of the herd.

While often called “huggable” because of their teddy-bear appearance, most alpacas tend to be stand-offish. They generally do not like human touch, although they will tolerate it when it becomes time for normal husbandry tasks, like cutting toe nails and checking their teeth. Male alpacas have some vicious canines with which they can do serious damage to a competitor’s testicles. It may sometimes be necessary to grind these down.

Males will readily form bachelor herds, and if kept out of sight of females will co-exist peacefully. However, if females are visible, the males may become quite aggressive towards each other. It is not uncommon to see them wrestle each other to the ground, ram each other’s chests, or even attempt to castrate each other with their sharp “fighting teeth” (which should be removed as soon as they erupt at age 2-3).

Alpacas tend to be most active in the morning and at dusk. It is not uncommon to see play behaviour in the late afternoon and early evening, especially with the youngsters. They will chase each other around the pastures at high speed, and will occasionally be found “pronking”. The pronk, as it is known, is a springing gait. The legs can hardly be seen to move as the animals jump about the pasture, often chasing each other, and clearly expressing joy. Truly a heart-warming sight!

They have excellent eyesight and will often spot things at a great distance, which we humans are unaware of. We have seen our herd give their warning call, noticing kudu on the hillside, or baboons in the tall grass, or jackal or some other unseen intruder at night. They can spot a strange dog from quite a distance, and the herd will gather together and sound alarm calls.

They have a wide range of vocalizations, the most common being a gentle “hum” – especially around feeding time – they must have built-in clocks! They have a distinct, loud and piercing alarm call. They can sometimes be heard clucking their tongues, usually towards their young.

Alpacas are extremely curious. Youngsters will often approach such novelties as birds in there pasture, obviously trying to figure out exactly what they are seeing. This can be an issue with things such as poisonous snakes, and snake bites are not uncommon – luckily the trampled remains of many have also been found in the paddock.

Their herd instinct is strong, and they form clear bonds with their herd mates. When a herd suffers a death, there are often signs of mourning. Likewise, when a former herd mate joins the herd (seen when we bought in more animals from our original source) the entire herd will excitedly run out to greet them. This herd bonding is striking, and in my opinion, sets them apart from ‘mere livestock’.

They can justly be called ‘regal animals’, fit for royalty, or the ‘gods’ – with reference to the Annunaki… Once upon a time, long, long ago, they were the ones keeping the alpaca… Ask Quetzalquatl… Or Pachama… They certainly predate all current religions!

Reproduction

Female alpacas are first bred from 14 – 18 months at which time they are called “hembras”. Female alpacas are induced ovulators, so they do not have an oestrus cycle and can be bred anytime. They are capable of producing one offspring a year for as many as 20 years. Alpaca mothers can often be rebred 2-3 weeks after giving birth. Alpaca’s typical breeding season is from the end of November to late April or early May, but they can have babies anytime. Female alpacas reach sexual maturity between 10 and 18 months of age. However, it is recommend that females reach two-thirds of their mature weight before being bred, i.e. 43kg. Male alpacas are unable to breed until adequate testicular growth has occurred and the penis is free from its attachments. Male alpacas reach breeding age at about 3 years, at which time they are called “machos”.

Breeding

Alpacas are induced ovulators. This means that unless they are mated, the female doesn’t ovulate.

They don’t have an oestrus cycle, but have a cycle of a different sort–hormones in the female alpaca stimulate both follicles within the ovary–The mature follicle forms a corpus luteum or CL that can be seen in an ultrasound and its size can indicate the readiness of the female to become pregnant.

To avoid the expense, alpaca breeders mate at fourteen day intervals. A female who is “ready” will sit in the “cushed” position. The male makes a distinctive “orgling” sound during the mating. When the female is pregnant, she will not be receptive and will kick or “spit” off the male.

Since females can be bred at any time (an alpaca vet can determine the growth of the CL and predict the “best” day for breeding.), males and females are usually kept in separate pens, in order to control who is bred when. Breeding can be done by selective breeding or pasture breeding. In selective or “hand” breeding, the dam and potential sire are put in a pen together. In pasture breeding, the male is put in a pasture with several females. We use breeding pens, and our males are paired to the appropriate females using special software, which allows us to determine the possible level of inbreeding, by tracking possible common ancestors.

Females can sometimes become pseudo pregnant. This is because 1/5 of male alpacas are sterile (probably because they are too young and are not totally developed). When female alpacas mate, they think they are pregnant and therefore they only mate once. Pregnant females may also absorb their pregnancies, usually in the first two months.

Birthing

The gestation period for an alpaca is approximately 11 months, producing only one cria (alpaca baby). Crias are often born between 9 am and 2 pm and usually without assistance. Rarely are crias born after 2 pm. Normal, healthy crias, weighing between 6.5 and 9kg, are standing within an hour of birth and nursing shortly after that.

Because alpacas are herd animals, when a cria is born, everyone else in the herd will come to take a look and welcome the new cria to the farm.

Females can be bred within a week or two after giving birth. The crias are generally weaned at six months or at least weighing 25kg.

To see how we interact with our alpaca, and for some more alpaca facts, head back to https://verlorevallei.com/, and to get closely aquainted to their fibre, you can browse our online store https://verlorevallei.com/online-store/and stay up to date with the latest rolag and bats for spinning, launched first on our Facebook page! https://www.facebook.com/Fibrewitch